Reviews

Highbrow

Shelley Horton-Trippe, in her recent exhibition High Brow Low Ride, references the great twentieth-century French writer Colette by way of a large painting titled The Pure and the Impure (Colette). Horton-Trippe draws on Colette’s book, The Pure and the Impure, where the writer attempts a deconstruction of the nature of the gender-bound self, particularly as it applies to women. Colette’s dialectical probing is one of the first literary examples of just how subjective the topic of gender and sexuality is—a topic that can never be contained by an either/or treatment. Colette herself was nothing if not a polymorphous perverse artist who considered her ravenous, desiring self as the ever-inquisitive product of an “ego in consonance with nature.” Horton-Trippe’s homage to Colette is a painting that is both delicate and bold, with passages that are fluid and garden-like, and as obdurate and opaque as stone. Her painting exudes a sexy lyricism—with its subtle male and female signifiers—and it is balanced by an area in the painting symbolizing a warped confusion in the guise of a tangle of painterly lines; but this tangle cannot resolve itself with a hopelessly pretty pink spatial allusion to a vagina that seems to be floating down from above; or perhaps it’s merely ascending from the confusion—powerful in its ascendancy and not afraid of its pictorial fragility. But there’s more: a distinctly phallic shape enters from the right edge of the painting, it too more delicate than dominating.

Although The Pure and the Impure (Colette) is not my favorite work in Horton-Trippe’s blockbuster show, nevertheless there is so much in it that meets the eye and then veers off into an abstract but intimate intention where the aim of the artist is not to resolve opposites so much as open up a space to meander in oppositional forces: the soft and the hard, the passive and the aggressive, pale fugitive color, and vividly anchored forms that have arisen from a constant search for meaning in a turbulent world. Yet Horton-Trippe knows that resolution is hard to come by even on a good day.

One of the most compelling works in the show, and indeed my favorite is Freak Flag, whose title belies the mystique of the painting’s Tantric-like essence in terms of visual imagery—there is an intense central blood-red triangle with rounded edges. Surrounding this shape are seven blue circles on an off-white ground. Eschewing superfluous brushstrokes in favor of a determined sense of wholeness, it’s as if Horton-Trippe scraped away her own propensity for painterly fugue states and set forth a personal sutra in visual terms about her need to embrace a metaphysical formality that aspires to a transcendental state. As Franck André Jamme wrote in his notes on the history of Tantric painting, “These works assemble almost everything in almost nothing.”

Freak Flag is an anomaly of sorts in Horton-Trippe’s dialectical flux—and it’s not a flag of truce so much as a prayer flag anchored within the artists relentless search for expression as she allows herself to be swept away to another patch of canvas in order to grapple with other contrasts between form and formlessness and the push and pull of yin/yang energy.

Horton-Trippe is an artist not bound by the life of a painter only. She is also an installation artist, a performer, and someone who works with moving images. This kind of multi-faceted creative personality can be both a blessing and a curse to the artistic process. For Horton-Trippe there is a need to tame the tiger, as it were, so the products of her creative drive can flow toward a coherent set of messages that in the end all emanate from her “temple of voluptuous devotions.”

Diane Armitage

Raising Fierce Beauty

How do we answer the question of finding art, beauty, love, hope in our current moment. As much as these might seem to be superficial, placating tropes, overly romantic or ineffective, there remains a deep desire to find solace through the visual world. In fact, in the face of the ceaseless onslaught of daily events, the drive to seek power and strength through creation has only grown stronger.

To me, art has always been synonymous with mothering. Again, the concept of mother, mothering, motherhood might seem to be soft and overtly feminine, much like beauty and art. But in my life, as the daughter of a bold artist, woman, mother, the potential of art to support life, growth, and change has been a daily lived experience. I have had the privilege of experiencing the process of this nurturing first-hand. The profound link between the fostering of an artwork and the fostering of a child is often neglected in art criticism and theory. So many of our most successful artists, particularly women artists, have been celebrated for their childlessness, as if art and children are mutually exclusive and art emerges as the higher calling. The fallacy in this determination is clear and yet the bias remains strong.

I explain this all in order to situate my emotional response to Shelley Horton-Trippe’s new body of work. I come to this work as daughter first, art historian second, which I firmly believe is the most honest path to this work that I can take. I have seen these paintings take shape over the last year as we stare down the horror of what our world has become. And I have seen these paintings grow from color sketches between my mother and my daughter, the seeds of splotches and patterns and lines and houses and flowers and pet dogs. I have seen the secret language between these two anchors of my life as they make together; a language that I witness but do not speak with them. But this is what I see, the private experience of these works. The brilliance here is how this private essence edges out to the viewer beyond our private realm of mother, daughter, granddaughter.

But then there is the work. The end result of the private process of making reaches beyond the internal and personal to the larger world of art history, politics, identity, philosophy, and popular culture. In High Brow Low Ride Shelley recalls the power of the Finish Fetish painters of 1960s Los Angeles (and Taos, of course). The high-gloss and bold colors of car culture, the sheen of Judy Chicago’s very early work, Ken Price’s vibrant, amorphous blobs. But she also, in the same moment, on the same surface, harkens back to the Romantics and the power of landscape as if she zooms in on those zones of abstracted washes and waves of color that are so utterly contemporary. Shelley’s paintings find a place for the past to merge with the present and for landscape to bump up against the hard sheen of a lowrider. This is where the hard and the soft can meet and it is a space that we are all seeking build and reside within.

Ultimately, in these paintings Shelley is willing into being a space for joy – as all mothers do. The architecture of her colors reveals a capacity for not only seeing alternatives to the mundane and the painful, but building them for all of us to escape into. The private gift comes to be the public revealing as it is nurtured and mothered from conception. The paint is applied in practiced layers. A balanced structure emerges from the possible chaos of sketched lines, rough brushstrokes, fading washes. The result is not just mother-comfort but a fierceness that we have all seen building to crescendo in recent months. These works are that beauty, love, hope that we need; the palliative and the propellant.

Bess Murphy, PhD

February 2018

Carbon

by Diane Armitage

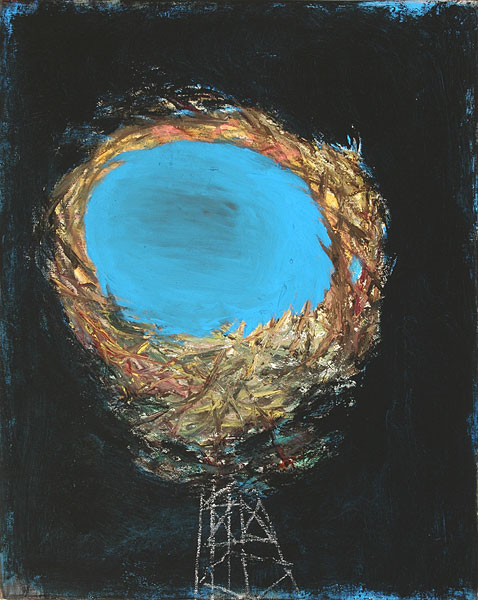

The paintings in Shelley Horton-Trippe’s recent show Carbon are the best of her career. The emotional authority they possess is so direct, damning, and volcanic that the viewer can only step back in amazed silence and let the artist’s sense of truth pour down in waves of metaphorical light, sweet crude.

It is as if these mostly black paintings, with their patches and particles of heart-grabbing, ravishing color, were conceived and executed in a series of convulsive, life-and-death struggles. And for all intents and purposes, they were. If in this work Horton-Trippe plays the role of the mythic Cassandra—delivering her apocalyptic visions of political strategies gone awry, greed blazing out of control, equivocation going down our gullets in a daily sacrament of selfishness and cynicism—Cassandra does not back down as she embraces her terribilità, the fierce beauty of her visions wed to their terrible truths.

Blackness too has its subtleties, its luminosity, and Horton-Trippe textures her pitch black, gives it inflections that make her dense atmospheres especially moving and piercing. In contrast to these dark surfaces, the artist has sketched oilrigs, for example, with their tops bursting into flames. The rigs look like a child could have drawn them, but they are perfect in their impact— signifiers that are anything but empty.

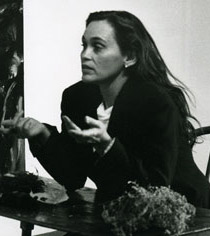

Shelley Horton-Trippe, performance from the Poem Paintings, 1991.

It isn’t just Horton-Trippe’s searing and insightful use of paint, however, that makes these paintings in her “carbon cycle” so riveting. It is also the way she has integrated pieces of fabric into the surfaces. In the painting Carbon, there is a collaged piece of material on the left with a pattern of pastel flowers, in the middle is the crumpled cloth of a small bean bag, and on the right, part of a man’s sport jacket lining in black silk—all that remains of the lining is an upside-down inner breast pocket with an elegant label embroidered in gold thread that reads, “made to order.” So many things are implied in this work—the explosion of reason, the death of civilization, the fiery conflagration of the progress of love. The made-to-order war in Iraq, with its legacy of blood, ashes, body parts, and occluded light, is just the beginning of Horton-Trippe’s multi-textual themes.

In her video Dictionary, featuring the artist, Horton-Trippe parses the meaning of the word “solipsism” as her hand passes a magnifying glass across a dictionary page. The definition of the word is that “the self can be aware of nothing but its own experiences and states.” After establishing the meaning of solipsism, the artist begins to cry in the video and as it ends, only the neck of the artist is visible in an intense close up. Head thrown back, Horton-Trippe’s neck becomes a heaving landscape of throttled emotion and impacted longing. There is nothing wasted, no false step, nothing trite or glib or slick in the transition between the Carbonpaintings and the artist’s long day’s journey into night.

Landscape as Idea

by Suzanne Deats from the book, New Mexico Landscape, 2006; Fresco Publications, Albuquerque, NM

One sees a landscape with all five senses, but one views a painting with the sense of vision alone. It is Shelley Horton-Trippe’s singular talent to be able to create a painting that conveys all the aspects of the land—the sound of tumbling water, the smell of the pines, the taste of the wind, and the warmth of the sun—in a way that even a sightless person might experience it. Her canvases are filled with emotions born of memory and empathy.

Horton-Trippe is so highly skilled that she is able to concentrate on feeling and take care of formal concerns on a subliminal level. Her work is entirely abstract, yet is landscape-based. “I paint a specific place, at a certain time of day, in an exact season of a particular year,” says the artist. “It’s so much about the moment when you’re remembering a situation. Maybe you want to capture it because you would like for it to last forever, yet you know it’s going to pass very quickly. There’s a sense of knowing that the sublime is so fleeting, and because of that there’s an underlying melancholy.”

Horton-Trippe’s childhood friend and longtime dealer, Carson See, is quick to point out that the somewhat sorrowful nuances evident in her darker images give the brighter ones more weight, and are crucial to an understanding of her entire body of art. “I have known her work all our lives,” he says, “and I have followed her happiness and her sadness. Her work is sexy and it is real because of the radiance of her spirit. She is not influenced by other postmodern artists, or by the market, or by current trends in art. She is utterly true to herself.”

Horton-Trippe has been a longtime presence in New Mexico, even though she has spent time intermittently in other places. She was living and working in Santa Fe during the heady days of the eighties, when the art scene burst forth exuberantly at a grassroots level. She was a full participant in the creative ferment that marked the era. In the years since, she has painted nonstop, taught college courses, and exhibited in the United States and abroad.

Throughout her career, she has continued to explore her deep ties to northern New Mexico. Her paintings are as strong and as moody as the landscape itself. Their color fields and intuitive lines may suggest skies or cliffs, or may echo the curve of a waterfall. A vertical cluster might be a forest; a bold circle is unmistakably the sun.

Horton-Trippe has immersed herself in the lore that brings the land to life. She speaks of a certain spot where the tumbling Rio Embudo empties into the Rio Grande. The local legend says that if you stand in the water there, you will find the love of your life within a year. She smiles and says, “I haven’t gone there yet.”